How Many Animals Have Gone Extinct Because Of Deforestation

How many species have gone extinct?

Extinctions have been a natural part of the planet'due south evolutionary history. 99% of the four billion species that have evolved on Earth are now gone.1 Virtually species take gone extinct.

Simply when people ask the question of how many species have gone extinct, they're usually talking about the number of extinctions in recent history. Species that have gone extinct, mainly due to human being pressures.

The IUCN Ruddy List has estimated the number of extinctions over the last 5 centuries. Unfortunately nosotros don't know virtually everything about all of the world's species over this period, so it's likely that some will have gone extinct without united states fifty-fifty knowing they existed in the first identify. So this is probable to exist an underestimate.

In the nautical chart nosotros see these estimates for different taxonomic groups. It estimates that 900 species have gone extinct since 1500. Our estimates for the better-studied taxonomic groups are likely to be more accurate. This includes 85 mammal; 159 bird; 35 amphibian; and 80 fish species.

To empathise the biodiversity problem nosotros demand to know how many species are nether pressure; where they are; and what the threats are. To do this, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species evaluates species beyond the world for their level of extinction risk. It does this evaluation every yr, and continues to expand its coverage.

The IUCN has not evaluated all of the globe'southward known species; in fact, in many taxonomic groups it has assessed only a very small percentage. In 2021, it had assessed just 7% of described species. But, this very much varies by taxonomic grouping. In the chart we meet the share of described species in each group that has been assessed for their level of extinction risk. Every bit we'd expect, animals such equally birds, mammals, amphibians accept seen a much larger share of their species assessed – more eighty%. But 1% of insects accept. And less than 1% of the world's fungi.

The lack of complete coverage of the globe's species highlights ii of import points nosotros demand to remember when interpreting the IUCN Red List information:

- Changes in the number of threatened species over time does not necessarily reflect increasing extinction risks. The IUCN Red List is a project that continues to aggrandize. More and more than species are been evaluated every yr. In the year 2000, less than xx,000 species had been evaluated. Past 2021, 140,000 had. Every bit more species are evaluated, inevitably, more volition exist listed as being threatened with extinction. This means that tracking the data on the number of species at gamble of extinction over time doesn't necessarily reflect an acceleration of extinction threats; a lot is just explained by an acceleration of the number of species being evaluated. This is why nosotros practice non show trends for the number of threatened species over time.

- The number of threatened species is an underestimate. Since only 7% of described species have been evaluated (for some groups, this is much less) the estimated number of threatened species is likely to be much lower than the actual number. There is inevitably more threatened species inside the 93% that accept not been evaluated.

Nosotros should also define more than clearly what threatened with extinction actually means. The IUCN Ruddy Listing categorize species based on their estimated probability of going extinct within a given period of fourth dimension. These estimates have into account population size, the rate of change in population size, geographical distribution, and extent of environmental pressures on them. 'Threatened' species is the sum of the post-obit three categories:

- Critically endangered species take a probability of extinction higher than l% in ten years or three generations;

- Endangered species have a greater than xx% probability in 20 years or v generations;

- Vulnerable have a probability greater than 10% over a century.

How many species are threatened with extinction?

The IUCN Red Listing has evaluated 40,084 species across all taxonomic groups to be threatened with extinction in 2021. Equally we noted before, this is a large underestimate of the true number considering near species take not been evaluated.

In the chart we see the number of species at risk in each taxonomic group. Since birds, mammals, and amphibians are the most well-studied groups their numbers are the most accurate reflection of the true number. The numbers for understudied groups such as insects, plants and fungi will be a big underestimate.

What percentage of species are threatened with extinction?

What share of known species are threatened with extinction? Since the number of species that has been evaluated for their extinction chance is such a small fraction of the total known species, information technology makes petty sense for usa to calculate this figure for all species, or for groups that are significantly understudied. It volition tell us very little virtually the actual share of species that are threatened.

But nosotros can summate it for the well-studied groups. The IUCN Red List provides this figure for groups where at least 80% of described species has been evaluated. These are shown in the chart.

Effectually i-quarter of the world's mammals; i-in-vii bird species; and xl% of amphibians are at run a risk. In more than niche taxonomic groups – such every bit horseshoe crabs and gymnosperms, nigh species are threatened.

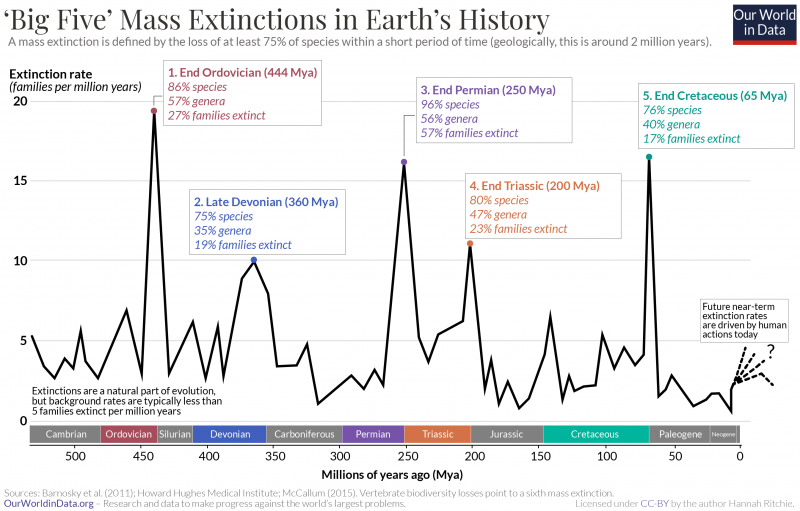

The 'Big 5' Mass Extinctions

Many people say we're in the midst of a sixth mass extinction. That man pressures on wild fauna – deforestation, poaching, overfishing and climate change – are pushing many of the world'south species to the brink. Before we await at whether there is any truth to this, we should accept a look at history's mass extinction events. When and why did they happen?

What is a mass extinction?

First we need to exist articulate on what we mean past 'mass extinction'. Extinctions are a normal part of development: they occur naturally and periodically over fourth dimension.two There'due south a natural groundwork charge per unit to the timing and frequency of extinctions: 10% of species are lost every million years; 30% every 10 one thousand thousand years; and 65% every 100 one thousand thousand years.3 It would exist wrong to presume that species going extinct is out-of-line with what we would expect. Evolution occurs through the remainder of extinction – the end of species – and speciation – the creation of new ones.

Extinctions occur periodically at what we would call the 'background rate'. We can therefore place periods of history when extinctions were happening much faster than this background rate – this would tell usa that at that place was an boosted ecology or ecological pressure creating more than extinctions than we would expect.

But mass extinctions are defined equally periods with much higher extinction rates than normal. They are divers by both magnitude and charge per unit. Magnitude is the percent of species that are lost. Rate is how quickly this happens. These metrics are inevitably linked, but we need both to qualify as a mass extinction.

In a mass extinction at to the lowest degree 75% of species go extinct inside a relatively (by geological standard) short period of time.four Typically less than two million years.

The 'Big Five' mass extinctions

There take been five mass extinction events in Globe's history. At to the lowest degree, since 500 million years ago; we know very trivial about extinction events in the Precambrian and early Cambrian before which predates this.5 These are called the 'Big 5', for obvious reasons.

In the chart nosotros see the timing of events in World'south history.6 Information technology shows the changing extinction rate (measured as the number of families that went extinct per meg years). Again, note that this number was never zero: background rates of extinction were low – typically less than v families per 1000000 years – but ever-nowadays through time.

We see the spikes in extinction rates marked as the five events:

- End Ordovician (444 million years ago; mya)

- Belatedly Devonian (360 mya)

- End Permian (250 mya)

- Stop Triassic (200 mya) – many people mistake this as the upshot that killed off the dinosaurs. But in fact, they were killed off at the end of the Cretaceous period – the fifth of the 'Large Five'.

- Terminate Cretaceous (65 mya) – the event that killed off the dinosaurs.

Finally, at the end of the timeline we have the question of what is to come. Perhaps we are headed for a sixth mass extinction. Merely we are currently far from that point. In that location are a range of trajectories that the extinction rate could take in the decades and centuries to follow; which one we follow is determined by usa.

What caused the 'Large V' mass extinctions?

All of the 'Big Five' were caused by some combination of rapid and dramatic changes in climate, combined with meaning changes in the limerick of environments on country or in the bounding main (such as ocean acidification or acrid pelting from intense volcanic activity).

In the tabular array here I item the proposed causes for each of the 5 extinction events.7

| Extinction Event | Age (mya) | Percentage of species lost | Cause of extinctions |

| End Ordovician | 444 | 86% | Intense glacial and interglacial periods created large swings in body of water levels and moved shorelines dramatically. Tectonic uplift of the Appalachian mountains created lots of weathering, sequestration of COii and with information technology, changes in climate and ocean chemistry. |

| Late Devonian | 360 | 75% | Rapid growth and diversification of state plants generated rapid and severe global cooling. |

| Stop Permian | 250 | 96% | Intense volcanic activity in Siberia. This caused global warming. Elevated CO2 and sulphur (HtwoS) levels from volcanoes caused bounding main acidification, acid pelting, and other changes in body of water and country chemistry. |

| End Triassic | 200 | lxxx% | Underwater volcanic activeness in the Key Atlantic Magmatic Province (Campsite) acquired global warming, and a dramatic modify in chemistry composition in the oceans. |

| End Cretaceous | 65 | 76% | Asteroid impact in Yucatán, United mexican states. This caused global cataclysm and rapid cooling. Some changes may have already pre-dated this asteroid, with intense volcanic activity and tectonic uplift. |

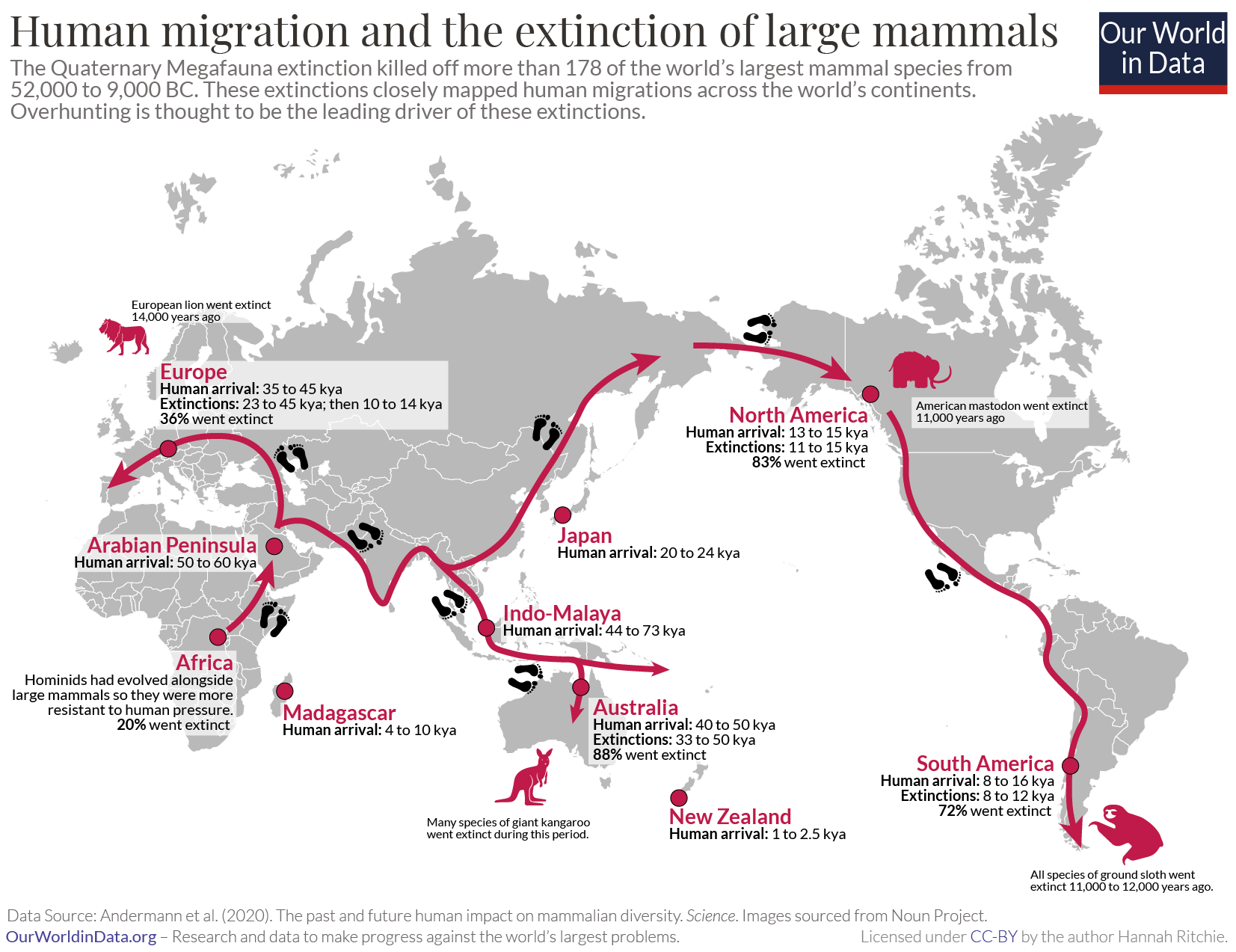

Quaternary Megafauna Extinctions

- Did humans cause the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction?

Humans have had such a profound impact on the planet's ecosystems and climate that Earth might be defined past a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene (where "anthro" means "man"). Some think this new epoch should start at the Industrial Revolution, some at the appearance of agriculture x,000 to 15,000 years agone. This feeds into the popular notion that environmental destruction is a recent phenomenon.

The lives of our hunter-gatherer ancestors are instead romanticized. Many think they lived in remainder with nature, unlike modern society where we fight against it. But when we await at the evidence of human impacts over millennia, it's difficult to see how this was true.

Our ancient ancestors drove more 178 of the world'southward largest mammals ('megafauna') to extinction. This is known every bit the 'Quaternary Megafauna Extinction' (QME). The extent of these extinctions across continents is shown in the chart. Between 52,000 and 9,000 BC, more than 178 species of the globe'due south largest mammals (those heavier than 44 kilograms – ranging from mammals the size of sheep to elephants) were killed off. At that place is strong evidence to advise that these were primarily driven by humans – we await at this in more than detail afterwards.

Africa was the least hard-hit, losing simply 21% of its megafauna. Humans evolved in Africa, and hominins had already been interacting with mammals for a long time. The same is too likely to exist true across Eurasia, where 35% of megafauna were lost. But Australia, Northward America and South America were particularly hard-hit; very soon after humans arrived, most large mammals were gone. Commonwealth of australia lost 88%; North America lost 83%; and Due south America, 72%.

Far from being in balance with ecosystems, very minor populations of hunter-gatherers inverse them forever. By 8,000 BC – almost at the end of the QME – at that place were simply effectually 5 million people in the globe. A few million killed off hundreds of species that nosotros will never get back.

Did humans crusade the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction?

The driver of the QME has been debated for centuries. Debate has been centered effectually how much was caused by humans and how much by changes in climate. Today the consensus is that most of these extinctions were caused past humans.

There are several reasons why we think our ancestors were responsible.

Extinction timings closely match the timing of man arrival. The timing of megafauna extinctions were not consistent across the world; instead, the timing of their demise coincided closely with the arrival of humans on each continent. The timing of human arrivals and extinction events is shown on the map.

Humans reached Australia somewhere between 65 to 44,000 years ago.8 Betwixt l and forty,000 years ago, 82% of megafauna had been wiped out. Information technology was tens of thousands of years before the extinctions in North and S America occurred. And several more before these occurred in Republic of madagascar and the Caribbean area islands. Elephant birds in Republic of madagascar were still present eight millennia afterward the mammoth and mastodon were killed off in America. Extinction events followed man's footsteps.

Significant climatic changes tend to be felt globally. If these extinction were solely due to climate nosotros would expect them to occur at a like time across the continents.

QME selectively impacted large mammals. In that location have been many extinction events in Earth'southward history. There have been five big mass extinction events, and a number of smaller ones. These events don't normally target specific groups of animals. Large ecological changes tend to bear upon everything from big to small mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish. During times of high climate variability over the past 66 million years (the 'Cenozoic period'), neither small nor large mammals were more vulnerable to extinction.9

The QME was different and unique in the fossil tape: it selectively killed off large mammals. This suggests a stiff influence from humans since nosotros selectively chase larger ones. There are several reasons why large mammals in detail have been at greater risk since the arrival of humans.

Islands were more heavily impacted than Africa. Every bit nosotros saw previously, Africa was less-heavily impacted than other continents during this period. Nosotros would expect this since hominids had been interacting with mammals for a long time earlier this. These interactions between species would have impacted mammal populations more than gradually and to a bottom extent. They may have already reached some form of equilibrium. When humans arrived on other continents – such every bit Australia or the Americas – these interactions were new and represented a step-alter in the dynamics of the ecosystem. Humans were an efficient new predator.

There has now been many studies focused on the question of whether humans were the key driver of the QME. The consensus is yep. Climatic changes might accept exacerbated the pressures on wild animals, but the QME can't be explained by climate on its ain. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were fundamental to the demise of these megafauna.

Homo impact on ecosystems therefore appointment dorsum tens of thousands of years, despite the Anthropocene image that is this a recent phenomenon. Nosotros've non only been in straight competition with other mammals, nosotros've also reshaped the landscape across recognition. Permit's take a look at this transformation.

Are we heading for a sixth mass extinction?

Seeing wild fauna populations shrink is devastating. But the extinction of an entire species is tragedy on some other level. It's not just a downwards tendency; it marks a stepwise alter. A complex life form that is lost forever.

But extinctions are nothing new. They are a natural part of the planet'south evolutionary history. 99% of the four billion species that accept evolved on Earth are now gone.10 Species become extinct, while new ones are formed. That's life. There's a natural background rate to the timing and frequency of extinctions: 10% of species are lost every meg years; 30% every 10 million years; and 65% every 100 one thousand thousand years.eleven

What worries ecologists is that extinctions today are happening much faster than nature would predict. This has happened five times in the past: these are defined as mass extinction events and are aptly named the 'Big V' [we cover them in more than detail here ]. In each extinction upshot the globe lost more than than 75% of its species in a brusque menses of time (hither we mean 'short' in its geological sense – less than two one thousand thousand years).

Are we in the midst of some other ane? Many have warned that we're heading for a sixth mass extinction, this one driven past humans. Is this really true, or are these claims overblown?

How do nosotros know if we're heading for a 6th mass extinction?

Before we can fifty-fifty consider this question we need to ascertain what a 'mass extinction' is. Most people would define it equally wiping out all, or about of, the world'southward wild animals. Only at that place'due south a technical definition. Extinction is adamant by two metrics: magnitude and rate. Magnitude is the per centum of species that take gone extinct. Charge per unit measures how quickly these extinctions happened – the number of extinctions per unit of measurement of time. These two metrics are tightly linked, but we demand both of them to 'diagnose' a mass extinction. If lots of species become extinct over a very long menses of time (allow'south say, i billion years), this is not a mass extinction. The rate is likewise slow. Similarly, if nosotros lost some species very quickly but in the finish information technology didn't amount to a big per centum of species, this also wouldn't authorize. The magnitude is too low. To exist defined as a mass extinction, the planet needs to lose a lot of its species apace.

In a mass extinction we need to lose more than 75% of species, in a curt period of time: around two 1000000 years. Some mass extinctions happen more quickly than this.

Of course, this is not to say that "only" losing 60% of the earth's species is no large bargain. Or that extinctions are the only measure of biodiversity we care most – large reductions in wildlife populations can cause just as much disruption to ecosystems as the complete loss of some species. We expect at these changes in other parts of our work [run into our commodity on the Living Planet Index ]. But here we're going to stick with the official definition of a mass extinction to exam whether these claims are true.

There are a few things that make this difficult. The first is just how little nosotros know well-nigh the globe'southward species and how they're changing. Some taxonomic groups – such as mammals, birds and amphibians – we know a lot about. We take described and assessed nigh of their known species. But nosotros know much less nearly the plants, insects, fungi and reptiles around u.s.a.. For this reason, mass extinctions are usually assessed for these groups we know almost nigh. This is mostly vertebrates. What we exercise know is that levels of extinction risk for the small number of plant and invertebrate species that accept been assessed is like to that of vertebrates.12 This gives us some indication that vertebrates might give united states of america a reasonable proxy for other groups of species.

The 2d difficulty is understanding mod extinctions in the context of longer timeframes. Mass extinctions tin happen over the course of a million years or more. We're looking at extinctions over the course of centuries or fifty-fifty decades. This means we're going to have to make some assumptions or scenarios of what might or could happen in the hereafter.

There are a few metrics researchers can utilize to tackle this question.

- Extinctions per million species-years (E/MSY). Using reconstructions in the fossil record, we tin summate how many extinctions typically occur every one thousand thousand years. This is the 'background extinction rate'. To compare this to current rates we can assess recent extinction rates (the proportion of species that went extinct over the past century or two) and predict what proportion this would be over one 1000000 species-years.

- Compare electric current extinction rates to previous mass extinctions. We can compare calculations of the current E/MSY to background extinction rates (equally above). Simply we tin as well compare these rates to previous mass extinction events.

- Calculate the number of years needed for 75% of species to become extinct based on current rates. If this number is less than a few million years, this would autumn into 'mass extinction' territory.

Calculate extinction rates for the past 500 years (or 200 years, or 50 years)and ask whether extinction rates during previous periods were every bit high.

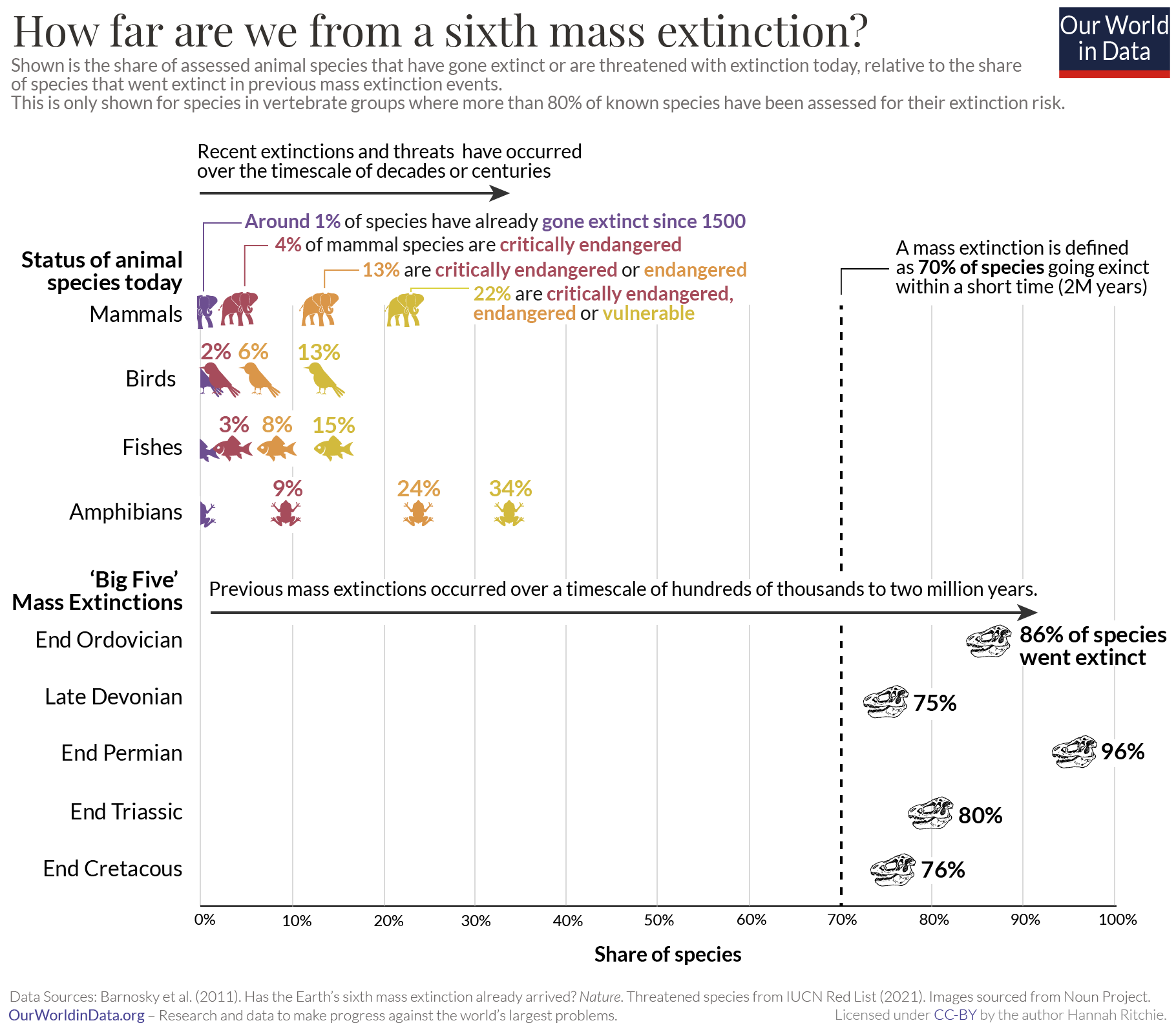

How many species accept gone extinct in contempo centuries?

An obvious question to ask is how many species have gone extinct already. How shut to the 75% 'threshold' are nosotros?

At first glance, it seems like we're pretty far away. Since 1500 around 0.5% to i% of the globe's assessed vertebrates accept gone extinct. As nosotros see in the nautical chart, that's around ane.3% of birds; i.four% of mammals; 0.six% of amphibians; 0.2% of reptiles; and 0.2% of bony fishes. Due to the many measurement issues for these groups – and how our understanding of species has inverse in recent centuries – the extinction rates that these predict are probable an underestimate (more on this subsequently).

So, nosotros've lost around 1% of these species. Simply nosotros should also consider the big number of species that are threatened with extinction. Thankfully we've non lost them yet, but there is a high gamble that nosotros do. Species threatened with extinction are defined by the IUCN Red List, and it encompasses several categories:

- Critically endangered species have a probability of extinction higher than l% in 10 years or three generations;

- Endangered species have a greater than twenty% probability in twenty years or five generations;

- Vulnerable have a probability greater than x% over a century.

There'due south a loftier run a risk that many of these species go extinct in the new few decades. If they practise, this share of extinct species changes significantly. In the nautical chart we likewise see the share of species in each group that is threatened with extinction. We would very quickly become from 1% to most one-quarter of species. We'd be one-third of the way to the '75%' line.

Again, you might think that 1%, or fifty-fifty 25%, is small. At to the lowest degree much smaller than the 75% definition of a mass extinction. But what's important is the speed that this has happened. Previous extinctions happened over the course of a 1000000 years or more. We're already far along the curve within but a few centuries, or even decades. We'll come across this more clearly afterward when we compare recent extinction rates to those of the past. But nosotros tin can quickly understand this from a quick dorsum-of-the-envelope calculation. If it took us 500 years to lose 1% of species, it would take usa 37,500 years to lose 75%.thirteen Much faster than the million years of previous extinction events. Of course this assumes that futurity extinctions would continue at the aforementioned rate – a big assumption, and one we will come to after. Information technology might fifty-fifty be a conservative i – there might be species that went extinct without us even knowing that they existed at all.

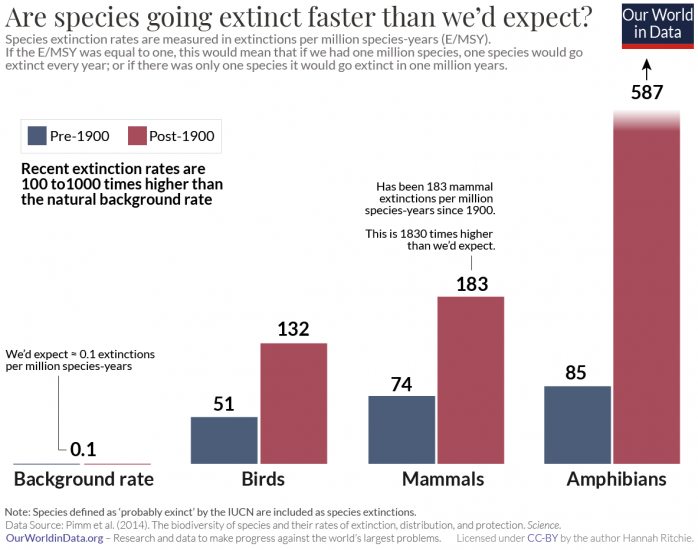

Are recent extinction rates higher than we would expect?

There are two ways to compare recent extinction rates. First, to the natural 'background' rates of extinctions. Second, to the extinction rates of previous mass extinctions.

The research is quite clear that extinction rates over the final few centuries take been much higher than nosotros'd look. The background rate of extinctions of vertebrates that nosotros would wait is around 0.ane to ane extinctions per 1000000-species years (E/MSY).xiv In the chart we encounter the comparison, broken downward by their pre- and postal service-1900 rates.

Mod extinction rates average effectually 100 E/MSY. This ways birds, mammals and amphibians have been going extinct 100 to thousand times faster than we would expect.

Researchers think this might fifty-fifty be an underestimate. One reason is that some modern species are understudied. Some might have gone extinct earlier we had the chance to place them. They volition ultimately show upwards in the fossil record afterward, only for now, we don't even know that they existed. This might exist particularly true for species a century agone when much less resource was put into wild animals research and conservation.

Another key point is that nosotros take many species that are not far from extinction: species that are critically endangered or endangered. There's a loftier chance that many could go extinct in the coming decades. If they did, extinction rates would increase massively. In another study published in Science, Michael Hoffman and colleagues estimated that 52 species of birds, mammals and amphibians move ane category closer to extinction on the IUCN Red Listing every year.15 Pimm et al. (2014) gauge that this would give us an extinction charge per unit of 450 E/MSY. Once again, 100 to 1000 times higher than the background rate.

How do recent extinction rates compare to previous mass extinctions?

Clearly we're killing off species much faster than would be expected. But does this autumn into 'mass extinction' territory? Is it fast enough to be comparable to the 'Big Five'?

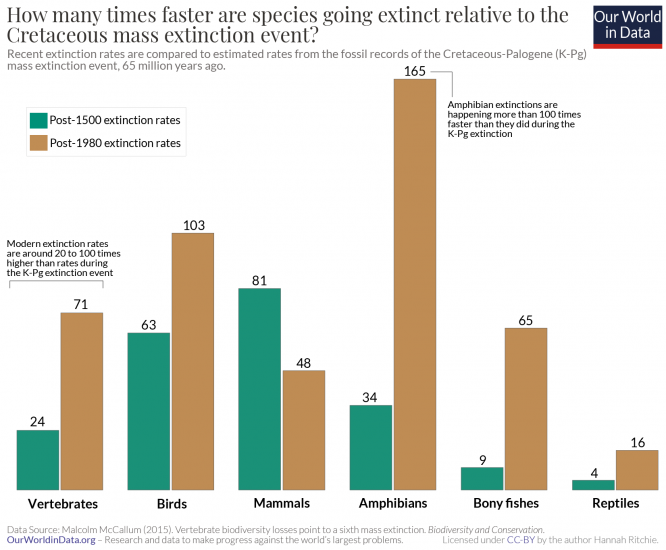

One fashion to reply this is to compare recent extinction rates with rates from previous mass extinctions. Researcher, Malcolm McCallum did this comparison for the Cretaceous-Palogene (K-Pg) mass extinction.16 This was the outcome that killed off the dinosaurs effectually 65 meg years ago. In the chart nosotros see the comparison of (non-dinosaur) vertebrate extinction rates during the One thousand-Pg mass extinction to contempo rates. This shows how many times faster species are now going extinct compared to then.

We see clearly that rates since the year 1500 are estimated to exist 24 to 81 times faster than the K-Pg event. If we await at even more recent rates, from 1980 onwards, this increases to up to 165 times faster. Again, this might even be understating the step of electric current extinctions. We take many species that are threatened with extinction: there is a high probability that many of these species go extinct within the next century. If we were to include species classified every bit 'threatened' on the IUCN Carmine List, extinctions would be happening thousands of times faster than the K-Pg extinction.

This makes the point clear: we're not just losing species at a much faster rate than we'd wait, nosotros're losing them tens to thousands of times faster than the rare mass extinction events in Earth's history.

How long would it have for us to reach the sixth mass extinction?

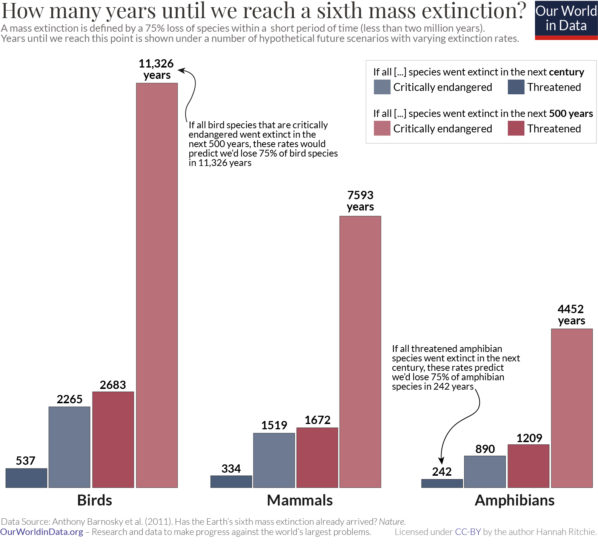

Recent rates of extinction, if they continued, would put us on class for a sixth mass extinction. A concluding way to cheque the numbers on this is to guess how long it would take for the states to become there. On our electric current path, how long before 75% of species went extinct? If this number is less than 2 one thousand thousand years, it would authorize equally a mass extinction event.

Earlier we came up with a rough estimate for this number. If information technology took u.s.a. 500 years to lose 1% of species, it would accept usa 37,500 years to lose 75%.17 That assumes extinctions go on at the average charge per unit over that time. Malcolm McCallum's assay produced a similar guild of magnitude: 54,000 years for vertebrates based on mail service-1500 extinction rates.18 Extinction rates have been faster over the by 50 years. Then if we take the post-1980 extinction rates, we'd get there fifty-fifty faster: in only 18,000 years.

Just once again, this doesn't business relationship for the large number of species that are threatened with extinction today. If these species did become extinct soon, our extinction rates would exist much college than the average over the last 500 years. In a written report published in Nature, Anthony Barnosky and colleagues looked at the fourth dimension it would take for 75% of species to get extinct beyond iv scenarios.19

- If all species classified as 'critically endangered' went extinct in the adjacent century;

- If all species classified equally 'threatened' went extinct in the side by side century;

- If all species classified as 'critically endangered' went extinct in the next 500 years;

- If all species classified as 'threatened' went extinct in the next 500 years.

To be clear: these are not predictions of the hereafter. We tin think of them equally hypotheticals of what could happen if we don't have action to protect the globe's threatened species. In each instance the causeless extinction rate would exist very different, and this has a significant impact on the time needed to cross the 'mass extinction' threshold. The results are shown in the chart.

In the most extreme example, where we lose all of our threatened species in the next 100 years, it would accept only 250 to 500 years earlier 75% of the globe'southward birds, mammals and amphibians went extinct. If only our critically endangered animals went extinct in the adjacent century, this would increase to a few thousand years. If these extinctions happened much slower – over 500 years rather than a century – information technology'd be around 5,000 to 10,000 years. In any scenario, this would happen much faster than the million twelvemonth timescale of previous mass extinctions.

This makes two points very clear. First, extinctions are happening at a rapid rate – upwards to 100 times faster than the 'Big Five' events that define our planet'south history. Current rates do point towards a sixth mass extinction. Second, these are scenarios of what could happen. Information technology doesn't have to exist this fashion.

The skillful news: we can preclude a sixth mass extinction

At that place is one thing that sets the 6th mass extinction apart from the previous five. It tin can exist stopped. We can stop it. The 'Big Five' mass extinctions were driven by a cascade of confusing events – volcanism, body of water acidification, natural swings in climate. At that place was no one or nothing to striking the brakes and turn things around.

This fourth dimension it's different. Nosotros are the primary driver of these environmental changes: deforestation, climate alter, ocean acidification, hunting, and pollution of ecosystems. That's depressing. But is also the best news nosotros could promise for. Information technology means we have the opportunity (and some would contend, the responsibleness) to end it. We can protect the world'due south threatened species from going extinct; we tin wearisome and contrary deforestation; irksome global climate alter; and let natural ecosystems to heal. There are a number of examples of where we take been successful in preventing these extinctions [run into our article on species conservation].

The determination that we're on class for a sixth mass extinction hinges on the assumption that extinctions will continue at their contempo rates. Or, worse, that they will advance. Goose egg about that is inevitable. To stop it, we need to sympathize where and why the world'southward species are going extinct. This is the beginning step to understanding what nosotros can do to turn things around. This is what our work on Biodiversity aims to attain.

How many species has conservation saved from extinction?

Information technology's hard to find practiced news on the land of the earth's wildlife. Many predict that we're heading for a sixth mass extinction; the Living Planet Index reports a 68% average decline in wildlife populations since 1970; and nosotros proceed to lose the tropical habitats that back up our virtually diverse ecosystems. The United nations Convention on Biological Diversity set twenty targets – the Aichi Biodiversity Targets – to be accomplished by 2020. The world missed all of them.20 We didn't run into a single one.

Perhaps, then, the loss of biodiversity is unavoidable. Possibly in that location is nothing nosotros can do to plough things around.

Thankfully there are signs of hope. As we will see, conservation activity might have been insufficient to meet our Aichi targets, simply it did make a difference. Tens of species were saved through these interventions. There's other testify that protected areas have retained bird diversity in tropical ecosystems. And each year there are a number of species that motility away from the extinction zone on the IUCN Red List.

We need to make certain these stories of success are heard. Of course, we shouldn't use them to mask the bad news. They definitely don't make upwardly for the large losses in wildlife we're seeing around the earth. In fact, the risk here is asymmetric: growth in i wildlife population does non starting time a species getting pushed to extinction. A species lost to extinction is a species lost forever. We tin can't brand up for this loss by merely increasing the population of something else. Only nosotros can make sure two messages are communicated at the same fourth dimension.

First, that nosotros're losing our biodiversity at a rapid charge per unit. 2nd, that it'southward possible to do something about it. If at that place was no promise of the second one being true, what would be the point of trying? If our deportment really made no difference then why would governments back up anymore conservation efforts? No, we need to exist vocal near the positives as well equally the negatives to make articulate that progress is possible. And, importantly, understand what we did right so that we can practise more of it.

In this article I want to take a wait at some of these positive trends, and better understand how we achieved them.

Pulling animals back from the brink of extinction

For anyone interested in wildlife conservation, losing a species to extinction is a tragedy. Saving a species is surely i of life's greatest successes.

Conservation efforts might accept saved tens of beautiful species over the final few decades. The 12th Aichi Target was to 'prevent extinctions of known threatened species'. Nosotros might have missed this, merely efforts have non been completely in vain.

In a recent study published in Conservation Letters, researchers guess that between 28 and 48 bird and mammal species would take gone extinct without the conservation efforts implemented when the Convention on Biological Diversity came into force in 1993.21 21 to 32 bird species, and 7 to sixteen mammal species were pulled back from the brink of extinction. In the last decade alone (from 2010 to 2020), 9 to eighteen bird, and 2 to vii mammal extinctions were prevented. This has preserved hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary history. It prevented the loss of 120 meg years of evolutionary history of birds, and 26 million years for mammals.

What this means is that extinction rates over the last two decades would accept been at to the lowest degree 3 to 4 times faster without conservation efforts.

This does not mean that these species are out-of-danger. In fact, the populations of some of these species is notwithstanding decreasing. We run into this in the chart, which shows how the populations of these bird and mammal species that were expected to have gone extinct are irresolute. sixteen% of these bird species, and 13% of the mammal species have gone extinct in the wild, but conservation has allowed them to survive in captivity. Beyond the critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable categories, 53% of bird and 31% of mammal species have increasing or stable populations. This is positive, simply makes clear that many of these species are however in refuse. Conservation has just been able to slow these losses downwardly.

This just looks at species on the brink of extinction. Many species in serious only less-threatened categories take been prevented from moving closer to extinction. Around 52 species of mammals, birds and amphibians move one category closer to extinction every yr. Without conservation, this number would be 20% higher.22

There are more than examples. Studies have shown that protected areas have had a positive impact on preserving bird species in tropical forests.23 These are some of the world'due south most threatened ecosystems. And while the IUCN Red Listing unremarkably makes for a depressing read, at that place are some success stories. This twelvemonth the European Bison, Europe's largest land mammals, was moved from 'Vulnerable' to 'Almost threatened' (significant information technology's less threatened with extinction) thanks to connected conservation efforts. We volition expect at more European success stories subsequently.

Friederike Bolam et al. (2021) looked at what conservation deportment were key to saving the mammal and bird species accounted to exist destined for extinction.24 For both birds and mammals, legal protection and the growth of protected areas was of import. Protected areas are non perfect – at that place are countless examples of poorly managed areas where populations continue to shrink. We will look at how constructive protected areas are in a follow-upwardly commodity. But, on average, they exercise make a difference. Clearly these efforts were critical for species that had gone extinct in the wild. Other important factors were controlling the spread of invasive species into new environments; reintroducing one-time species into environments where they had been previously lost; and restoring natural habitats, such as wetlands and forests.

Restoring wild animals populations beyond Europe

The European Bison might steal the headlines, but in that location are many adept news stories across Europe. Many of the drivers of biodiversity loss – deforestation, overhunting, and habitat loss – are happening in the tropics today. Just these same changes likewise happened beyond Europe and North America. Only, they happened earlier – centuries ago.

Europe is now trying to restore its lost wild fauna and habitats through rewilding programmes. The Zoological Lodge of London, Birdlife International and European Bird Census Council published a report which details how these efforts are going.25 They looked at how the populations of xviii mammal and nineteen of Europe'south iconic merely endangered bird species had changed over the by l years.

Most had seen an overwhelming recovery. Almost species saw an increase of more than 100%. Some saw more than 1000% growth. Brown bear populations more than doubled over these 50 years. Wolverine populations doubled in the 1990s alone. The Eurasian lynx increased by 500%. Reintroduction programmes of the Eurasian beaver saw populations increase by 14,000% – a doubling or tripling every decade.

What were the principal drivers of this recovery?

Part of Europe'due south success in restoring wildlife populations in recent decades tin can exist attributed to the fact that their development and harvesting of resources came long agone. My European ancestors had already hunted many species to extinction; expanded agricultural state into existing woods; and built cities, roads and other infrastructure that fragments natural habitats. But in our very recent past have European countries been able to reverse these trends: reforesting; raising livestock instead of hunting; and now reducing the amount of land we use for agriculture through improved productivity.

But there have also been a number of proactive interventions to restore populations. In the chart here we encounter the main drivers of recovery beyond European bird species. At the top of the list is habitat restoration – the re-institution of wetlands, grasslands, forests and other national habitats. Reintroduction of species has also been key. Just protecting existing habitats and species has been equally important. Legal site protections and bans on shooting accept been the main recovery drivers of virtually every bit many species.

After millennia of habitat loss and exploitation by humans, wildlife is coming back to Europe. Somewhat ironically, humans have played an of import role in this.

While almost biodiversity trends point towards a barren time to come for the planet'southward wildlife, there are success stories to draw upon. These should non brand us complacent, or deflect our attention from the seriousness of these losses. But I think information technology is important to highlight what we have achieved. Protecting the world's wild animals is not impossible – nosotros've simply seen the counter-evidence to this. To commit to wider conservation efforts we demand to shout more loudly nigh these wins. Otherwise policymakers will turn their backs on them and we will lose many cute species that we could and should accept saved.

Explore more of our work on Biodiversity

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/extinctions

Posted by: youngtwored.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Animals Have Gone Extinct Because Of Deforestation"

Post a Comment